How to Design GOOD Test Cases

Testing for software is hard. Good test cases can help you increase maintainability and stability of your code, while bad test cases not only can not benefit you, some things can even slow down your development process.

It is good to see many test cases written in our team now, but some of them are not really benefit our team and even become burden of the development. I think part of the reason is because we don’t have instructions for how to design good test cases that really help us out. So I’d like to build a basic framework about how to write test cases in UT and E2E.

In order to understand the reason why frameworks are constructed that way, we need to learn generic knowledge of testing first. We will discuss this in a bit.

Why do We Need Tests?

In order to write good test cases, we need to understand our goals. There are lots of reasons why we need tests when we develop software. Here is the most obvious one:

- Safe from bugs: To ensure our software is correct today and correct in the unknown future.

As your software grows, you will inevitably need to verify more and more logic in order to ensure your modification of code is correct and doesn’t break something that already exists accidentally. Automatic testing is a good way to reduce the cost of verifying.

Why Software Testing is Hard?

The key challenge of software testing are two things:

- The space of possible test cases is generally too big to cover exhaustively. Let say we wanna test a 32-bit floating-point multiply operation, a*b. There are 2(64) test cases!

- Software behavior varies discontinuously and discretely across the space of possible inputs. For example, if we wanna test abs(a)function, it behaves differently when a < 0 and a >= 0.

The system may seem to work fine across a broad range of inputs, and then abruptly fail at a single boundary point.

Therefore, test cases must be chosen carefully and systematically.

Warm Up: Design Test Cases for Multiply Function

1 | /** |

What is a good test suite for this function?

Systematic Testing

Systematic testing means that we are choosing test cases in a principled way, with the goal of designing a test suite with three desirable properties:

- Correct. A correct test suite accepts all legal implementations of the spec. This gives us the freedom to change the implementation internally without having to change the test suite.

- Thorough. A thorough test suite finds as many actual bugs in the implementation as possible.

- Small. We wanna write fewer test cases while keeping it thorough.

Choosing test cases by partitioning

Software usually has a wide range of input values that produce different behaviors in different ranges. We want to pick a set of test cases that are small enough to be easy to write and maintain and quick to run, yet thorough enough to find bugs in the program.

To do this, we divide the input space into partitions, each consisting of a set of inputs.

Then we choose one test case from each partition, and that’s our test suite.

The idea behind partitions is to divide the input space into sets of similar inputs on which the program has similar behavior.

Let’s look at abs(a) function:

1 | /** |

We focus on where this function will produce different behaviors in input space:

- When

a >= 0,abs()returnsa. - When

a < 0,abs()returns-a.

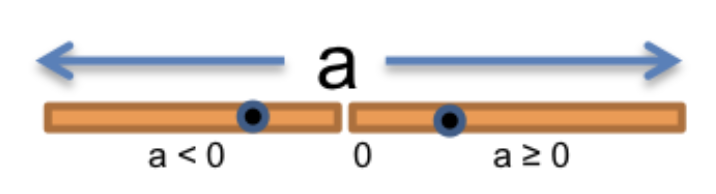

So we can divide the input space a: number into a < 0 and a >= 0 partitions like this:

And then we pick one test case from each partition and form our test suite:

1 | // case 1: negative input |

Include boundaries in the partition

Bugs often occur at boundaries between partitions. Some examples:

- 0 is a boundary between positive numbers and negative numbers

- the maximum and minimum values of numeric types, like

Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGERorNumber.MAX_VALUE. - emptiness for collection types, like the empty string, empty array, or empty set

- the first and last element of a sequence, like a string or array

Why are these boundaries dangerous? Here are two main reasons:

- programmers often make off-by-one mistakes, like writing

<=instead of<, or initializing a counter to 0 instead of 1. - boundaries may be places of discontinuity in the code’s behavior: When a number variable used as an integer grows beyond

Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER, for example, it suddenly starts to lose precision.

So we can add another test case in our abs() test suite:

1 | // case 1: negative input |

Cover Multiple Partition in The Same Test Case

In the previous example, we use pick one input of a partition as one test case. That’s nice. But as the program becomes more complex and there are multiple dimensions of inputs, we might face the issue that even if we just pick one test case for one partition, the number of combinations of inputs is still overwhelming, so that it breaks the rule that we want our test suite to be small and fast.

1 | Let's take a look at the multiply example: |

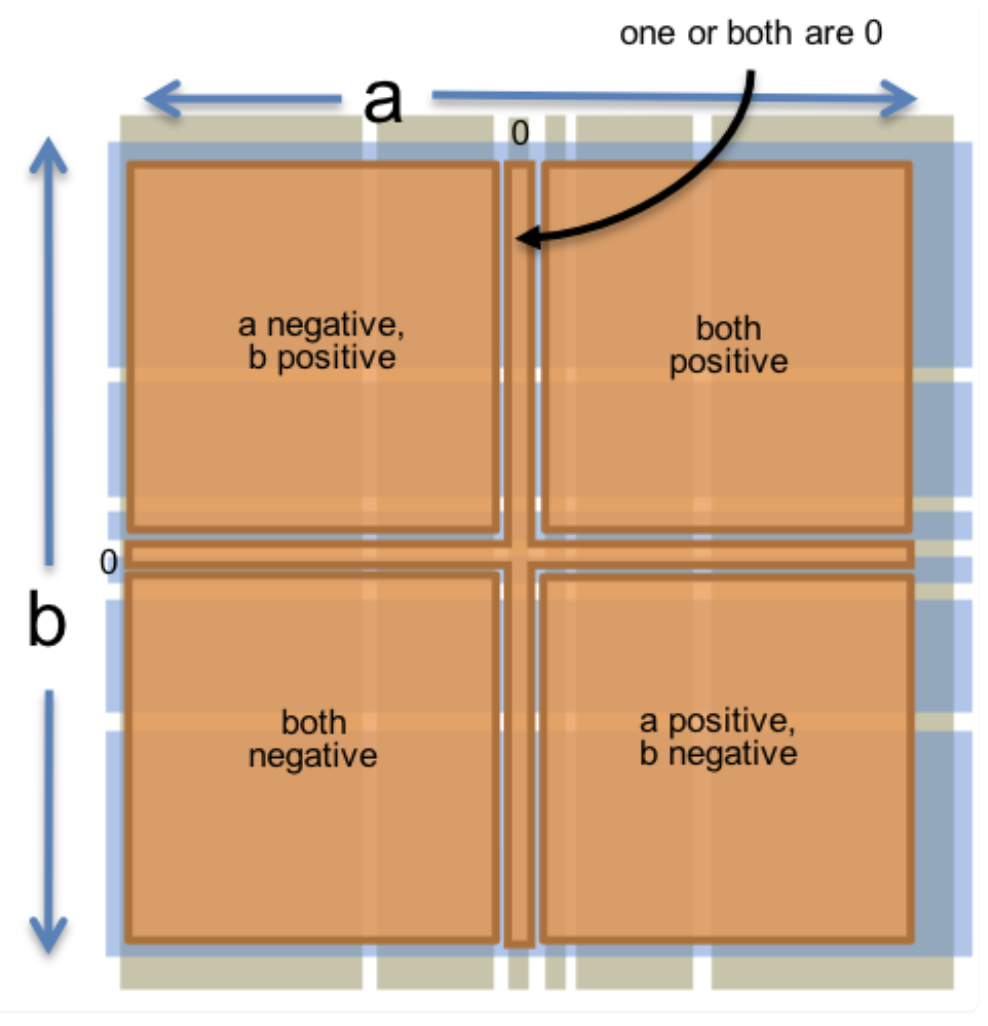

This function has a two-dimensional input space, consisting of all the pairs of integers (a,b). According to the rules of multiplication, we can separate the input space into these partitions:

- a and b are both positive.The result is positive

- a and b are both negative.The result is positive

- a is positive, b is negative. The result is negative

- a is negative, b is positive. The result is negative

And then, we add the boundary cases:

- a or b is 0, because the result is always 0

- a or b is 1, the identity value for multiplication

To ensure that it works when the input number is very large, we also need to test Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER, Number.MIN_SAFE_INTEGER. So we have: - a or b is small or large (i.e., small enough to represent exactly in a number value, or too large for a number)

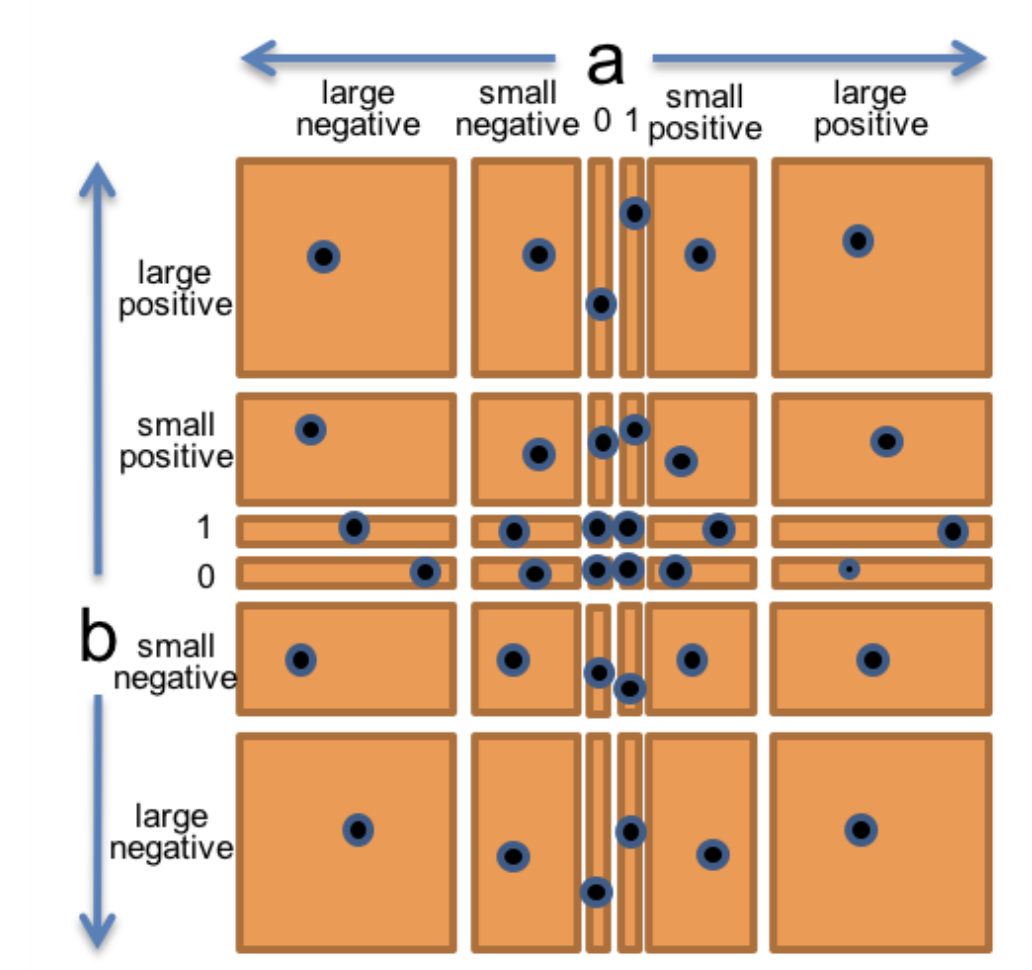

After separate each dimension into:

- 0

- 1

- small positive integer (≤ Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER and > 1)

- small negative integer (≥ Number.MIN_SAFE_INTEGER and < 0)

- large positive integer (> Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER)

- large negative integer (< Number.MIN_SAFE_INTEGER)

We end up having a complex partitions graph like this:

If we pick one test case(dots on the graph) for each partition, there are 36 combinations. That’s a lot! This is a so-called combinatorial explosion. And this is only two dimensions.

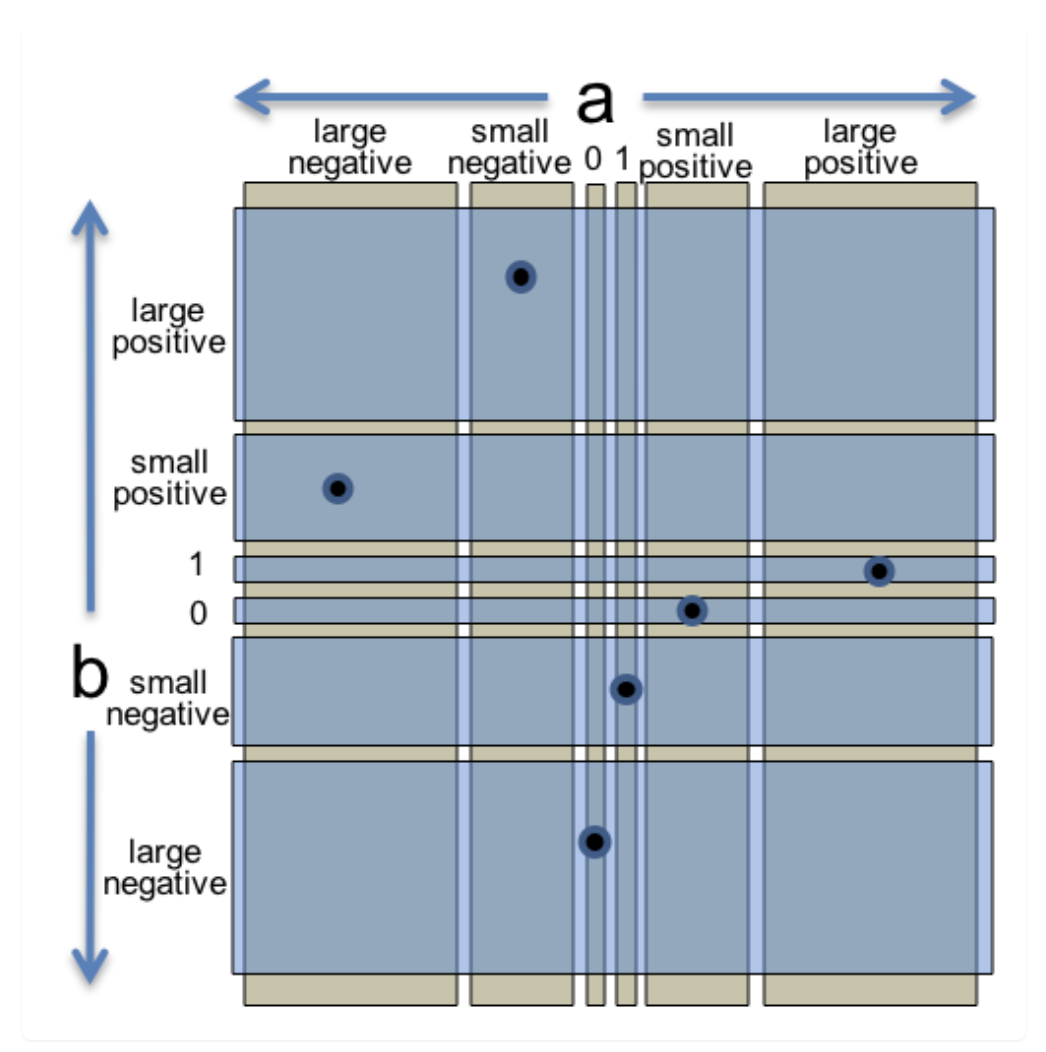

How to solve it? We realize that our test cases increase as the dimensions increase: O(n) = s^n where s is the partitions for each dimension, and n is the number of dimensions. And we are repeatedly covering the same partition from a single dimension perspective. So we can treat the features of each input a and b as two separate partitions of the input space. One partition only considers one value:

1 | // partition on a: |

And then we combine those values together without repeating them. We can form a test suite that covers all partitions of each dimension, and the complexity won’t increase when dimensions increase: O(n) = s.

This indeed increases the risk of bugs, but we can add another layer of partition to cover some of the combinations:

1 | // a and b are both positive, a is a small integer, b is a LARGE_NUMBER |

Software Engineering, Testing — Apr 10, 2024

Made with ❤ and at Earth.